Texto del 23/02/2017

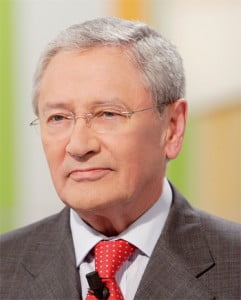

FRANCESC XAVIER DOMÈNECH SAMPERE

Sabadell (Barcelona)

Concienciado activista e inquieto investigador de los movimientos sociales, se ha erigido en el político mejor valorado del Principado. Es partidario de una Catalunya con múltiples soberanías en un Estado plurinacional, y defiende la celebración de un referéndum que permita a los catalanes decidir su futuro. Su preocupación principal, no obstante, reside en la superación de una crisis que considera sistémica y que, a su entender, nos ha llevado a las puertas de un nuevo ciclo histórico.

Ver texto completo. Elija el idioma:

[expand title=»Español» />» trigclass=»arrowright»]

Activista político e investigador histórico

Mi vida la definen dos trayectorias. Por una parte, la implicación en el activismo político, que se inició en mi ya lejana adolescencia, cuando apenas contaba catorce años. La segunda es mi pasión por la historia, que me ha llevado a convertirme en doctor, investigador y profesor en la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, especializado en movimientos sociales y cambios políticos. Mi faceta activista se acentuó a partir del 2008, ante la cínica gestión de la crisis que acababa de iniciarse. Participé intensamente en el movimiento del 15-M, en las formulaciones de la nueva política, en la propuesta del Procés Constituent en Catalunya y fui designado como cabeza de lista en Barcelona por En Comú Podem, convirtiéndome en diputado del Congreso en 2015 y revalidando mi acta al año siguiente.

Quebrantamiento del pacto territorial

Existen tres factores que explicarían el Procés. En primer lugar, un longevo y fallido encaje de Catalunya en España; una asignatura pendiente históricamente hablando, vinculada a la corriente política mayoritaria que abarca desde el catalanismo conservador hasta el más popular y radical, y que ha tenido como vocación la construcción de la nación catalana a la vez que ha mantenido el espíritu de transformación del Estado español. A ello se le unen la sentencia del Tribunal Constitucional de 2010, que no solo mermó el Estatuto catalán, sino quebró la voluntad del pueblo de Catalunya y, tácitamente, el pacto territorial contemplado en la Constitución de 1978; y la crisis económica, en especial, su gestión, que fue percibida como la gran imposición de los poderes no votados por encima de las voluntades democráticas, lo que generó reacciones diversas en distintas áreas geográficas. En Catalunya, esta situación se canalizó como reclamación de soberanía.

Por una auténtica democracia

El movimiento del 15-M denunciaba que lo que se presentaba como democracia no era tal y abogaba por un sistema en el que de verdad decidiera el pueblo. En Catalunya, a esta reivindicación se le sumó la de la dignidad nacional y la reclamación de soberanía. La nueva política surgida de este movimiento tiene que ver con la crisis de legitimidad del sistema político y de las viejas organizaciones, así como de sus seculares protagonistas; porque ahora se evidencia que la retórica de que la democracia otorga el poder al pueblo es falsa. En el caso de las izquierdas tradicionales mayoritarias, la crisis es tanto de sus líderes como programática, ya que sus políticas son contrarias a lo que encarnan sus principios ideológicos y fundacionales.

La historia de un gran cambio político

A los masivos movimientos de protesta ante el statu quo pueden añadirse datos objetivos, como el hecho de que el bipartidismo, que en Europa concentraba en 2009 el 81% de los votos, pasó a sumar apenas el 49% en 2014. A nivel local, lo que algunos vaticinaban como un fenómeno efímero, del 15-M hemos pasado a ganar las elecciones municipales en Barcelona, a liderar los comicios legislativos en Catalunya en las dos últimas citas y a convertirnos en la tercera fuerza en España. Es la historia de un gran vacío político y una extraordinaria respuesta.

No hemos nacido para llenar un vacío

Hemos asistido a una gran mutación económica, social, cultural y política. Pero no hemos nacido para llenar un vacío. Si nuestra formación acude a las instituciones solo para cubrir dicho vacío, no cambiaremos nada ni estaremos atacando en profundidad retos tan preocupantes como los de un sistema económico que muestra profundos síntomas de agotamiento, donde la economía especulativa está sobredimensionada frente a la productiva, o que asiste impasible a la degradación del medio ambiente. Mario Benedetti decía: «Cuando teníamos todas las respuestas nos cambiaron las preguntas». Ahora el reto es conocer las nuevas preguntas y explorar cuáles tienen que ser las nuevas respuestas.

Sin duda, se negociará

Tengo la sensación de que la construcción de la nueva Catalunya se hará desde el Principado, pero de que existirá un punto clave que se desarrollará en Madrid; porque asistimos a una importante acumulación de fuerzas y de desafíos. Salvo que los planes del Presidente Puigdemont giren en torno a la Ley de Transitoriedad Política (cuyos resultados me generan muchas dudas), habrá un momento clave de negociación; ignoro su trasfondo, pero sin duda se negociará.

Un nuevo Estado requiere una alta participación

Para construir un nuevo Estado, es necesaria una alta participación, por lo que para llevar a cabo un referéndum es necesario movilizar a la mayoría de la población. Y aunque es cierto que la Comisión de Venecia defiende que no se sitúe un umbral de participación para evitar que los partidarios del «no» promuevan la abstención, no me gusta que el Presidente Puigdemont aluda a ella a menudo, porque significa que, de entrada, ya está renunciando a una parte importante del pueblo de Catalunya.

De un 20% a un 44% de españoles favorables al referéndum catalán

Hay una tarea que no puede hacerse de la noche a la mañana, como es la de conseguir amplios apoyos en el Estado. Y no se trata solo de convencer a distintos partidos, sino de obtener respaldos sociales. Que nuestra formación hermana, Podemos, defendiendo el referéndum, haya logrado resultados notorios en Sevilla o en Cádiz evidencia un cambio de ciclo. Nuestras encuestas internas revelan que el porcentaje de españoles favorables al referéndum apenas superaba en 2013 el 20%, lo que viene a ser la población de Catalunya y el País Vasco juntas. Actualmente, gira en torno al 44%. Aunque para quienes muestran prisa en independizarse este porcentaje puede significar poco, desde una perspectiva histórica supone una evolución enorme.

Autonomía solo para vascos y catalanes

Lo realmente importante del federalismo reside en el reconocimiento. Porque de poco sirve una etiqueta de Estado federal si se limita a ser una simple evolución de un Estado autonómico. Cuando los padres de la Constitución de 1978 en su artículo 2 decidieron aludir a nacionalidades y regiones estaban reconociendo la existencia de identidades diferenciadas. Y con ello pretendían resolver el encaje del País Vasco y Catalunya, porque el desarrollo del Estado de las Autonomías no estaba previsto. En ese aspecto, irónicamente coincido con Esperanza Aguirre, figura relevante del PP que defiende que solo vascos y catalanes deberían gozar de Estatuto de Autonomía. El caso de Navarra resulta paradójico, porque su estatus es el de Estado libre asociado. Ni siquiera tiene estatuto de autonomía, sino la Ley de Reintegración y Amejoramiento del Régimen Foral de Navarra; texto de lectura única que solo puede modificarse a través de una negociación bilateral entre el Gobierno español y el navarro.

Debates más transgresores en 1978 que en la actualidad

Al haber entrado a formar parte de la Comisión Constitucional del Congreso, he tenido ocasión de documentarme mucho en torno a la redacción de la Carta Magna. He constatado que, entonces, en 1978, los debates fueron mucho más plurales y abiertos frente al enroque que exhiben ahora los más arduos defensores de esa misma Constitución. Miquel Roca, con quien no coincido ideológicamente, argumentaba que ese texto suponía una trans-ferencia de las soberanías de las naciones originarias hacia una nueva nación constitucional. Y Gregorio Peces-Barba, otro «padre» de la Constitución, hablaba de nación de naciones, reconociendo que había naciones no españolas, en clara alusión a Catalunya. Respecto a los debates actuales, aquello era enormemente transgresor.

Un monarca que no ha sabido legitimarse

Personalmente, pensaba que en una situación como la actual acabaría emergiendo una solución de tipo monárquico. No porque la desee, sino porque, si bien el Rey emérito contaba con una legitimidad en ejercicio derivada de su papel en el golpe de Estado del 23-F (que propició que la población no se considerara monárquica pero sí juancarlista), el monarca actual no goza de esa legitimidad. De hecho, accede a la Corona en un entorno de crisis, con un sistema político que adolece de propuestas y que a duras penas exhibe capacidad para gobernar y mantenerse en el poder. Así las cosas, creía que el nuevo Rey buscaría una legitimidad articulada en torno a una solución para Catalunya. Pero viendo su inoperancia hasta el momento, pienso que la crisis institucional se agudizará porque no es posible gobernar sin ideas durante mucho tiempo.

Constituciones que acaban cayendo por empecinamiento

Desearía que se abriera la caja de Pandora de los procesos constituyentes. El catedrático de Derecho Constitucional Javier Pérez Royo afirma que las constituciones españolas siempre propician debates sobre sus posibles reformas para acabar siendo sustituidas por otras. Ante el empecinamiento en no reformarlas, acaban diluyéndose. Por tanto, solo puede ocurrir que el viejo sistema político reaccione y empiece a hallar soluciones a la crisis, la corrupción, la desigualdad social… o acabaremos desembocando en una nueva disposición constituyente.

[/expand]

[expand title=»English» />» trigclass=»arrowright»]

Doctor of History and M.P. in the Spanish Congress, representing En Comú Podem

A fervent activist and a historian with an interest in social movements, he is the best-valued politician in Catalonia. He believes in a Catalonia with sovereign powers in a plurinational state and defends a referendum that will allow the Catalan people to decide its future. His main concern, however, lies in overcoming a crisis that he believes is systemic and, in his opinion, has taken us to the dawn of a new historical cycle.

A political activist and historian

My life has two paths. Firstly, involvement in political activism which I became interested in when I was younger, at the tender age of fourteen. Secondly, my passion for history, which led me to become a Doctor of History, researcher and lecturer at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, specialising in social movements and political changes. During the course of 2008, my activist side grew stronger after witnessing the cynical management of the crisis that had just begun. I played an important part in the 15-M movement, in new political formulations, and in the Procés Constituent proposal in Catalonia, and I was the first name on the list of En Comú Podem in Barcelona. In 2015, I became a Congress M.P. and was re-elected the following year.

Breach of the territorial pact

There are three reasons for the Procés. Firstly, the longstanding and difficult insertion of Catalonia in Spain; this has historically been a pending issue, linked to the majority political current that ranges from conservative Catalanism to the more popular and radical Catalan sentiment with a calling to create the Catalan nation, while maintaining the spirit of transformation of the Spanish state. This situation was aggravated by the ruling of the Constitutional Court in 2010, which led to the paring of the Catalan statute, which was also against the will of the Catalan people and tacitly contravened the territorial pact included in the Constitution of 1978. It was also the result of the economic crisis, and in particular, its management, which was perceived as a major imposition of non-voted powers that went against the democratic wish of the people, generating different reactions in different geographical regions. In Catalonia, this situation gave rise to a demand for sovereignty.

Towards true democracy

The 15-M movement denounced a democracy that was not perceived as such and advocated a system in which the people could decide. In Catalonia, this claim was accompanied by a movement in favour of national dignity and a cry for sovereignty. The new political situation that arose from this movement has to do with the legitimisation of the political system and of old organisations, and their secular protagonists. Because it is now clear that the rhetoric democracy grants power to the people is false. In the case of traditional left-wing majorities, the crisis has affected its leaders and is programmatic, because their policies are contrary to the ideas embodied in their ideological and foundational politics.

The history of a huge political change

We can add objective data to mass movements that protest against the status quo, such as the fact that the two-party system, which in 2009 concentrated 81% of the votes in Europe, now stands at barely 49% in 2014. On a local scale, we have passed from the 15-M movement, which some considered a passing phenomenon, and winning the municipal elections of Barcelona, to leading the past two legislative elections in Catalonia and becoming the third political force in Spain. This is the history of a huge political void and an extraordinary response.

We were not set up to fill a void

We have witnessed a huge economic, social, cultural and political mutation, but we were not set up to fill a void. If our party enters the institutions merely to fill that void, we will not change anything and be unable to deal with an important challenge, namely attacking an economic system that is showing signs of exhaustion, in which speculative economics are overtaking productive economics, or one that remains impassive to the degradation of the environment. In the words of Mario Benedetti: “They changed the questions when we had all the answers”. Now, the challenge is to find out what the new questions are and see what the new responses must be.

I am sure that a negotiated solution will be found

I have the feeling that the new Catalonia will be created here in our land, but with a key aspect that will be implemented in Madrid, because we are witnessing an important gathering of forces and challenges. Unless the plans of President Puigdemont are based on the Ley de Transitoriedad Política or Disconnection Law, (and I have serious doubts about its results), a key moment will arise in the negotiation; I have no idea about the underlying current, but I have no doubt that the solution will be negotiated.

A new state requires mass participation

To build a new state, there must be mass participation, and so to hold a referendum it will be necessary to mobilise the majority of the population. It may be true that the Venice Commission states that there is no participation threshold to prevent those voting “no” from promoting abstention, I do not like to hear President Puigdemont refer to it repeatedly as this means he is renouncing an important part of the Catalan people.

Between 20% and 44% of the Spanish population are in favour of the Catalan referendum

There is one task that cannot be performed in one day, namely to obtain wide consensus in the Spanish state. It is not merely a question of convincing different parties, but of obtaining social support. The fact that our sister party, Podemos, which defends the referendum, has achieved splendid results in Seville or Cádiz proves the existence of a change in cycle. Our internal surveys show that the percentage of the Spanish population in favour of the referendum was barely 20% in 2013, which is the equivalent to the population of both the Basque Country and Catalonia. Right now, this percentage stands at around 44%. Despite the fact that this percentage may seem small to those who are eager for independence, from a historical standpoint, it is an important evolution.

Autonomy only for the Basque and Catalan people

The most important aspect of federalism lies in recognition. The label of a federal state will be of little use if it is limited to a mere evolution of an autonomous state. When the authors of article 2 of the Constitution of 1978 decided to refer to nationalities and regions, they were admitting the existence of national identities. They used this to resolve the issues of the insertion of the Basque Country and Catalonia because the implementation of the State of Autonomies was not envisaged. Ironically enough, I agree in this respect with Esperanza Aguirre, an important member of Partido Popular, who defends that only the Basque and the Catalan populations should have an Autonomous Statute. The case of Navarre is also a paradox, because its status is that of a free associated state. It has no statute of autonomy, but the Ley de Reintegracion y Amejoramiento del Régimen Foral de Navarra, a text for single reading that can only be modified in a bilateral negotiation between the Spanish government and the government of Navarre.

The debates of 1978 were much more direct than the debates of today

After becoming a member of the Congress Constitutional Commission, I had the occasion to study the drafting of the Spanish Constitution. I realised that in 1978, the debates were much more plural and open as opposed to the currently deadlock of the most fervent defenders of the Constitution. Miquel Roca, with whom I do not coincide in terms of ideology, argued that this text implied a transfer of the sovereignties of original nations to a new constitutional nation. Gregorio Peces-Barba, another “father” of the Constitution, spoke of a nation of nations, admitting that there were non-Spanish nations, in a clear reference to Catalonia. That was really laying it on the line, unlike the debates of today.

A monarch who was never legitimised

Personally, I always thought that in a situation such as this, the monarchy would propose a solution. Not because I wanted it to, but because although the former king was legally exercising his role due to his part in the 23-F coup (which caused the population to declare itself in favour of Juan Carlos, but not in favour of the monarchy), the monarch of today does not enjoy that legitimisation. In fact, he became king at a time of crisis, with a political system that lacked ideas and is barely able to govern and remain in power. In this situation, I thought the new king would try to find a legitimate way out and a solution for Catalonia. However, after witnessing his current inability to do so, I think that the institutional crisis will worsen, because it is impossible to govern without ideas for very long.

Constitutions that fall due to obstinacy

I sincerely hope that the Pandora’s Box of constituent processes is opened. The Constitutional Law Professor Javier Pérez Royo says that Spanish constitutions always encourage debate about their possible reforms and are always replaced with others. In view of the obstinacy of refusing to reform them, they always disappear. The only solution is for the old political system to react and start to find a solution to the crisis, corruption, social inequality, or we will finally end up with a new constituent system.

[/expand]

[expand title=»Français» />» trigclass=»arrowright»]

Docteur en histoire et député d’En Comú Podem au Congrès

Activiste sensibilisé et avide chercheur de mouvements sociaux, il est devenu l’homme politique le mieux noté de Catalogne. Il est partisan d’une Catalogne avec plusieurs souverainetés dans un État plurinational et défend la célébration d’un référendum qui permette aux catalans de décider de leur futur. Nonobstant, sa principale préoccupation réside dans la résolution d’une crise qu’il considère systématique et qui, à son avis, nous a conduits aux portes d’un nouveau cycle historique.

Activiste politique et chercheur historique

Ma vie a été marquée par deux trajectoires. D’une part, l’implication dans l’activisme politique qui a commencé alors que je n’avais que quatorze ans. La seconde est ma passion pour l’histoire, qui m’a conduit à devenir docteur, chercheur et professeur à l’Universitat Autònoma de Barcelone, spécialisé en mouvements sociaux et changements politiques. Ma facette activiste s’est accentuée à partir de 2008, face à la gestion cynique de la crise qui commençait. J’ai participé intensément au mouvement du 15-M, aux formulations de la nouvelle politique, à la proposition du Procés Constituent en Catalogne et j’ai été désigné comme tête de liste d’En Comú Podem à Barcelone, devenant député au Congrès en 2015, puis réélu l’année suivante.

Violation du pacte territorial

Il existe trois facteurs qui expliqueraient le Procés. En premier lieu, un emboîtement obsolète et manqué de la Catalogne au sein de l’Espagne ; une « écharde dans le pied du point de vue historique, liée au courant politique majoritaire qui englobe tant le catalanisme conservateur que le plus populaire et radical, et qui visait la construction de la nation catalane, tout en maintenant l’esprit de transformation de l’État espagnol. Il faut ajouter à cela la décision du Tribunal Constitutionnel de 2010, qui a réduit le statut catalan et bafoué la volonté des citoyens catalans et tacitement, le pacte territorial contenu dans la Constitution de 1978 ; et la crise économique, en particulier sa gestion, qui a été perçue comme la grande imposition des pouvoirs non votés, au détriment des volontés démocratiques, ce qui a donné lieu à diverses réactions dans différentes zones géographiques. En Catalogne, cette situation a été canalisée sous forme de réclamation de souveraineté.

En faveur d’une démocratie authentique

Le mouvement du 15-M dénonçait que ce que l’on présentait comme une démocratie n’en était pas une et plaidait pour un système qui soit vraiment décidé par les citoyens. En Catalogne, à cette revendication est venue s’ajouter celle de la dignité nationale et de la réclamation des souverainetés. La nouvelle politique surgie de ce mouvement est liée à la crise de légitimité du système politique et des vieilles organisations, ainsi que leurs protagonistes séculaires ; car on voit aujourd’hui que la rhétorique selon laquelle la démocratie donne le pouvoir aux citoyens est fausse. Dans le cas des gauches traditionnelles majoritaires, la crise est autant de leurs dirigeants que pragmatique, car leurs politiques sont contraires à ce qu’incarnent leurs principes idéologiques et de fondation.

L’histoire d’un grand changement politique

Aux mouvements massifs de protestation contre le statu quo viennent s’ajouter des données objectives, comme le fait que le bipartisme qui en 2009 en Europe concentrait 81 % des votes, n’en réunissait plus que 49 % en 2014. Au niveau local, nous avons remporté les élections municipales à Barcelone, nous sommes arrivés en tête des deux dernières élections législatives en Catalogne et sommes devenus la troisième force politique d’Espagne, alors que certains parlaient de phénomène éphémère. C’est l’histoire d’un grand vide politique et d’une réponse extraordinaire.

Nous n’avons pas vu le jour pour combler un vide

Nous avons assisté à une grande mutation économique, sociale, culturelle et politique. Mais nous n’avons pas vu le jour pour combler un vide. Si notre formation arrive aux institutions dans le seul but de combler ce vide, nous ne changerons rien et n’attaquerions pas non plus en profondeur des défis aussi alarmants que ceux d’un système économique qui présente de graves symptômes d’épuisement, où l’économie spéculative est surdimensionnée face à la productive, ou qui assiste impassible à la dégradation de l’environnement. Mario Benedetti disait : « C’est quand on croit posséder toutes les réponses, qu’on s’aperçoit qu’on a changé les questions ». Désormais, le défi consiste à connaître les nouvelles questions et à explorer quelles doivent être les nouvelles réponses.

Il ne fait aucun doute qu’il y aura une grande place pour la négociation

J’ai la sensation que la construction de la nouvelle Catalogne se fera à partir du Principat, mais qu’il y aura un point-clé qui se développera à Madrid ; car nous assistons à une importante accumulation de forces et de défis. À moins que les plans du président Puigdemont tournent autour de la Loi de Transitoriété Politique (dont les résultats me font douter), il y aura un moment clé de négociation ; j’ignore son arrière-plan, mais il ne fait aucun doute qu’il y aura une grande place pour la négociation.

Un nouvel État exige une grande participation

Pour construire un nouvel État, il faut une grande participation et pour mener à bien un référendum il faut mobiliser la majorité de la population. Il est certes vrai que la commission de Venise défend de ne pas décréter un seuil de participation pour éviter que les partisans du « Non » favorisent l’abstention, mais je n’aime pas que le président Puigdemont y fasse souvent allusion, car cela signifie qu’il renonce d’entrée de jeu à une partie importante des citoyens catalans.

Entre 20 % et 44 % des espagnols sont favorables au référendum catalan

Nous ne pouvons pas obtenir de vastes soutiens au sein de l’État du jour au lendemain. Et il ne s’agit pas seulement de convaincre différents partis, mais d’obtenir des soutiens sociaux. Que notre formation sœur, Podemos, qui défend le référendum, ait obtenu des résultats notoires à Séville ou à Cadix témoigne d’un changement de cycle. Nos sondages internes révèlent qu’en 2013, le pourcentage d’espagnols favorables au référendum dépassait à peine les 20 %, soit la population de Catalogne et du Pays Basque réunis. Actuellement, elle avoisine les 44 %. Or, pour ceux qui ont hâte de devenir indépendant, ce pourcentage peut paraître peu, mais du point de vue historique, il implique une énorme évolution.

Autonomie uniquement pour les Basques et les Catalans

L’importance du fédéralisme réside dans la reconnaissance. À quoi sert une étiquette d’État fédéral si elle se limite à être une simple évolution d’un État autonomique. Lorsque les pères de la Constitution de 1978 décidèrent de citer les nationalités et régions dans l’article 2, ils reconnaissaient en fait l’existence des identités différenciées et voulaient ainsi résoudre la place du Pays Basque et de la Catalogne, car le déve-loppement de l’État des Autonomies n’était pas prévu. En ce sens, et ironie du sort, je suis d’accord avec Esperanza Aguirre, figure importante du PP qui défend que seuls les Basques et les Catalans devraient bénéficier du Statut d’Autonomie. Le cas de Navarre est paradoxal car son statut est celui de l’État libre associé. Il n’a même pas de statut d’autonomie, mais la Loi de réincorporation et d’amélioration du Régime du Fuero de Navarre ; un texte de lecture unique qui ne peut être modifié qu’à travers une négociation bilatérale entre le Gouvernement espagnol et celui de Navarre.

Des débats plus transgresseurs en 1978 qu’aujourd’hui

En rejoignant la Commission Constitutionnelle du Congrès, j’ai eu l’occasion de me documenter énormément au sujet de la rédaction de la Carta Magna. Et j’ai constaté qu’en 1978, les débats étaient beaucoup plus « pluriels » et ouverts face au roque qu’exhibent aujourd’hui les défenseurs les plus ardus de cette même Constitution. Miquel Roca, dont je ne partage pas l’idéologie, argumentait que ce texte impliquait un transfert des souverainetés des nations originaires vers une nouvelle nation constitutionnelle. Et Gregorio Peces-Barba, autre « père » de la Constitution, parlait d’une nation de nations, et reconnaissait qu’il y avait des nations non espagnoles, en faisant clairement allusion à la Catalogne. Or, cela était énormément transgresseur, comparé aux débats actuels.

Un monarque qui n’a pas su se légitimer

Personnellement, je pensais que dans une situation comme l’actuelle, une solution de type monarchique verrait le jour. Pas parce que je le souhaite, mais parce que si le roi émérite comptait sur une légitimité dans l’exercice dérivé de son rôle dans le coup d’état du 23-F (qui entraîna la population à se considérer non pas monarchique mais juancarlista), le monarque actuel ne possède pas cette légitimité. D’ailleurs, il accède à la couronne dans un cadre de crise, avec un système politique qui manque cruellement de propositions et qui peine à exhiber la capacité de gouverner et de maintenir le pouvoir. Je pensais que le nouveau roi chercherait une légitimité articulée autour d’une solution pour la Catalogne. Mais en voyant son inefficacité jusqu’à présent, je pense que la crise institutionnelle s’accentuera car il est impossible de gouverner longtemps sans idées.

Des constitutions qui finissent pas tomber à cause de l’obstination

Je souhaiterais que la boîte de Pandore des processus constituants s’ouvre. Le professeur agrégé de droit constitutionnel, Javier Pérez Royo a affirmé que les constitutions espagnoles favorisent toujours des débats sur de possibles réformes mais sont finalement remplacées par d’autres. Face à l’obstination de ne pas les réformer, elles finissent par se diluer. Par conséquent, la seule chose qui peut se produire est que le vieux système politique réagisse et commence à trouver des solutions contre la crise, la corruption, l’inégalité sociale… le cas contraire nous déboucherons sur une nouvelle disposition constituante.

[/expand]

[expand title=»Deutsch» />» trigclass=»arrowright»]

Doktor der Geschichte und Abgeordneter im spanischen Kongress für die Partei En Comú Podem

Als bewusster Aktivist und neugieriger Erforscher der gesellschaftlichen Bewegungen hat er sich in einen der am meisten geschätzten Politiker Kataloniens verwandelt. Er tritt für ein Katalonien mit multiplen Hoheitsgewalten in einem plurinationalen Staat ein und Durchführung eines Referendums ein, mit dem die Katalanen über ihre Zukunft entscheiden können. Hauptsächlich Sorge bereitet ihm jedoch die Überwindung einer Krise, die er für systemisch ansieht und die uns seiner Meinung nach zu einem neuen historischen Zyklus geführt hat.

Politischer Aktivist und Geschichtsforscher

Mein Leben wird von zwei Trajektorien definiert. Einerseits die Beteiligung am politischen Aktivismus seit meiner inzwischen weit zurückliegenden Jugend, als ich lediglich 14 Jahre alt war. Zweitens meine Leidenschaft für die Geschichte, die mir einen Doktortitel, Forschungstätigkeiten und den Posten eines Professors an der Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona mit dem Fachgebiet gesellschaftliche Bewegungen und politische Änderungen eingebracht hat. Meine Rolle als Aktivist verstärkte sich ab dem Jahr 2008 angesichts der zynischen Handhabung der gerade begonnenen Krise. Ich nahm an den unter der Bezeichnung ‚Bewegung 15. Mai‘ bekannten Demonstrationen, an der Formulierung der neuen Politik sowie dem Vorschlag des verfassunggebenden Procés in Katalonien teil und kam schließlich auf den ersten Listenplatz der Partei En Comú Podem in Barcelona, sodass ich 2015 als Abgeordneter des spanischen Kongresses gewählt wurde.

Verletzung des Territorialpakts

Drei Faktoren erklären den Procés. Erstens eine langwierige und gescheiterte Einfügung Kataloniens in Spanien; eine historisch offene Aufgabe, die mit der mehrheitlichen politischen Strömung verknüpft ist und sich vom konservativen bis hin zum radikalsten Katalanismus erstreckt. Ziel war hierbei, die katalanische Nation zu schaffen und gleichzeitig den Umwandlungsgeist des spanischen Staates zu bewahren. Dazu kommt das Urteil des spanischen Verfassungsgerichts aus dem Jahr 2010, das nicht nur das katalanische Autonomiestatut schmälerte, sondern den Willen des katalanischen Volkes und implizit den in der Verfassung des Jahres 1978 festgelegten Territorialpakt brach. Drittens die Wirtschaftskrise und insbesondere der Umgang mit derselben, der als die Machtdurchsetzung der nicht gewählten Kräfte gegenüber dem demokratischen Willen wahrgenommen wurde, was zu unterschiedlichen Reaktionen in mehreren geografischen Bereichen führt. In Katalonien kanalisierte sich diese Situation als Forderung der Souveränität.

Für eine echte Demokratie

Die Bewegung 15. März prangerte an, dass das, was als Demokratie verkauft wurde, gar nicht demokratisch war, und forderte ein System, in dem das Volk entscheiden sollte. In Katalonien kam zu dieser Forderung die nationale Würde und Souveränität. Die aus dieser Bewegung entstandene neue Politik steht in Verbindung mit der Legitimationskrise des politischen Systems und der alten Organisationen sowie deren weltlicher Vertreter. Denn jetzt hat sich die Falschheit der Rhetorik erwiesen, dass in der Demokratie die Macht beim Volk liegt. Im Fall der traditionellen mehrheitlichen Linken umfasst die Krise sowohl deren Führer als auch das Programm, da die von den linken Parteien angewandte Politik ihren ideologischen Grundsätzen widerspricht.

Die Geschichte eines großen politischen Wandels

Zu den Massenprotestbewegungen gegen den Status quo kommen objektive Daten wie die Tatsache, dass das Zweiparteiensystem, das in Europa 2009 81 der Wählerstimmen ausmachte, 2014 nur noch auf 49 % kam. Auf lokaler Ebene haben wir es geschafft, die Kommunalwahlen in Barcelona zu gewinnen, bei den beiden letzten Parlamentswahlen in Katalonien zu führen und uns in die drittstärkste Kraft in Spanien zu verwandeln. Dies ist die Folge eines großen politischen Vakuums und einer außergewöhnlichen Reaktion.

Unser Ziel ist es nicht, ein Vakuum zu füllen

Wir haben an einem grundlegenden wirtschaftlichen, gesellschaftlichen, kulturellen und politischen Wandel teilgenommen. Unser Ziel ist es jedoch nicht, ein Vakuum zu füllen. Wenn unsere Partei sich nur an den Institutionen beteiligt, um dieses Vakuum zu füllen, dann werden wir nichts verändern und so besorgniserregende Herausforderungen wie die eines Wirtschaftssystems bewältigen, das starke Erschöpfungssymptome aufweist. Ein Wirtschaftssystem, in dem die spekulative Wirtschaft gegenüber der produktiven überdimensioniert ist und das die Verschlechterung unserer Umwelt teilnahmslos zulässt. Schon Mario Benedetti sagte: „In dem Moment, in dem wir glauben, alle Antworten zu haben, ändern sich plötzlich alle Fragen.“ Die Herausforderung besteht jetzt darin, die neuen Fragen zu kennen und die neuen Antworten zu erarbeiten.

Es wird zweifellos zu Verhandlungen kommen

Ich habe das Gefühl, dass die Errichtung des neuen Kataloniens vom Fürstentum ausgehen, ein wesentlicher Punkt jedoch in Madrid entwickelt wird: denn wir stehen vor einer erheblichen Ansammlung von Stärken und Herausforderungen. Sofern sich die Pläne des Präsidenten Puigdemont nicht um das Gesetz der Transitoriedad Política (Gesetz über den juristischen Übergang) drehen (dessen Ergebnisse in mir viele Zweifel auslösen), wird es zweifellos zu wichtigen Verhandlungen kommen.

Ein neuer Staat erfordert eine hohe Beteiligung

Zur Errichtung eines neuen Staats ist eine hohe Beteiligung erforderlich, sodass zur Durchführung eines Referendums die Mehrheit der Bevölkerung mobilisiert werden muss. Obwohl die Kommission von Venedig die Ansicht vertritt, dass die Beteiligung keine Grenze darstellen darf, damit die Befürworter des „Neins“ nicht die Stimmenthaltung fördern können, gefällt es mir nicht, dass Präsident Puigdemont diese häufig anspricht. Denn dies bedeutet den Verzicht auf einen wichtigen Teil des katalanischen Volkes.

44 % der Spanier befürworten inzwischen ein katalanisches Referendum

Es gibt Aufgaben, die man nicht von heute auf morgen erledigen kann, beispielsweise eine breite staatliche Unterstützung zu erreichen. Dabei handelt es sich nicht nur darum, politische Parteien zu überzeugen, sondern einen gesellschaftlichen Rückhalt zu gewinnen. Dass unsere Schwesterpartei Podemos trotz ihres Eintretens für ein Referendum bemerkenswerte Resultate in Sevilla oder Cádiz erzielt hat, beweist einen Wechsel. Unsere internen Umfragen belegen, dass der Prozentsatz der Spanier zugunsten eines Referendums 2013 wenig mehr als 20 % betrug, was ungefähr der Summe der Bevölkerung von Katalonien und dem Baskenland entspricht. Derzeit liegt dieser Prozentsatz bei 44 %. Obwohl dies denjenigen, die schnell unabhängig werden wollen, gering erscheinen mag, bedeutet er historisch gesehen dennoch eine enorme Entwicklung.

Autonomie nur für Basken und Katalanen

Entscheidend für den Föderalismus ist die Anerkennung. Denn der Aufkleber eines föderalistischen Staats ist wenig wert, wenn sich dieser auf eine simple Evolution eines Staats der Autonomien beschränkt. Als die Väter der spanischen Verfassung von 1978 beschlossen, im Artikel 2 auf die Nationalitäten und Regionen hinzuweisen, erkannten sie damit die Existenz unterschiedlicher Identitäten an. Ziel war es, die Einfügung des Baskenlandes und Kataloniens zu lösen, da die Entwicklung des Autonomiestatuts nicht vorgesehen war. In dieser Hinsicht stimmt ich ironischerweise mit Esperanza Aguirre überein, eine wichtige Person der PP, die sagt, dass ein Autonomiestatut nur Basken und Katalanen verliehen werden könne. Der Fall Navarra erscheint wie ein Paradox, da Navarra den Status eines freien Mitgliedsstaats besitzt. Navarra besitzt noch nicht einmal ein Autonomiestatut, sondern verfügt lediglich über ein Gesetz zur Reintegration und Verbesserung des Partikularrechts von Navarra, das nur mit einem bilateralen Abkommen zwischen der spanischen und navarrischen Regierung geändert werden kann.

Offenere Debatten 1978 als heute

Dank meiner Teilnahme an der verfassungsrechtlichen Kommission des Kongresses hatte ich Gelegenheit, mich umfassend über den Text der Verfassung zu informieren. Dabei konnte ich feststellen, dass die Debatten im Jahr 1978 im Vergleich zum aktuellen Standpunkt vieler strenger Verteidiger derselben Verfassung wesentlich pluralistischer und offener waren. Miquel Roca, mit dem ich ideologisch nicht übereinstimme, argumentierte, dass dieser Text eine Übertragung der Hoheitsgewalten der ursprünglichen Nationen an eine neue verfassunggebende Nation bedeutete. Und Fregorio Peces-Barba, ein weiterer Vater der Verfassung, sprach von der Nation der Nationen und erkannte damit in klarer Anspielung auf Katalonien an, dass es nicht-spanische Nationen gab. Gegenüber den aktuellen Debatten war dies enorm übergreifend.

Ein Monarch, der es nicht verstanden hat, sich zu legitimieren

Persönlich hatte ich gedacht, dass in einer Lage wie der aktuellen eine monarchische Lösung entwickelt würde. Nicht etwa, weil ich diese wünsche, sondern weil der ehemalige König dank seiner Rolle beim Staatsstreich vom Februar über eine Legitimierung verfügte (dieser Putsch führte dazu, dass die Bevölkerung nicht die Monarchie, sondern Juan Carlos unterstützte). Der aktuelle Monarch verfügt nicht über eine derartige Legitimierung. Tatsächlich wurde er inmitten einer Krise und eines politischen Systems ohne Vorschläge gekrönt, das kaum in der Lage war, zu regieren und sich an der Macht zu halten. Aufgrund dieser Umstände dachte ich, der neue König würde sich zwecks Legitimierung für eine Lösung für Katalonien einsetzen. Angesichts seiner bisherigen Untätigkeit glaube ich jedoch inzwischen, dass sich die institutionelle Krise nur noch verschärfen wird, da es nicht möglich ist, solange ohne Ideen zu regieren.

Verfassungen, die wegen Sturheit scheitern

Ich wünschte, man würde in den verfassunggebenden Prozessen die Büchse der Pandora öffnen. Der Professor für Verfassungsrecht Javier Pérez Royo erklärt, die spanischen Verfassungen haben immer Debatten über mögliche Reformen ausgelöst, seien jedoch schließlich immer durch andere ersetzt worden. Angesichts der Sturheit, keine Reformen durchzuführen, werden diese schließlich verwässert. Die einzige Möglichkeit ist daher, dass das alte politische System reagiert und beginnt, Lösungen für die Krise, Korruption, soziale Ungleichheit usw. Zu finden… anderenfalls wird es schließlich zu einer neuen verfassunggebenden Verfügung kommen.

[/expand]